Sacred Sites

Sacred sites – Architecture and popular expressions

Sacred sites – Architecture and popular expressions

a travelling exhibition staged in

UNESCO, Paris,2003

Albert-Kahn Museum, Boulogne, 2005

Oslo City Hall, 2005

Stockholm City Hall, 2006

Folkteatern i Gävleborg, Gävle, Sweden, 2006

Artistic expressions of the sacred, in cultures, religions and beliefs throughout the world, are the common denominator of this exhibition. By highlighting the inter-relationships of popular, aesthetic and architectural forms, they enable us to perceive their particularities, similarities and differences.

Claude Lévi-Strauss reminds us « It is the difference between cultures that makes their meeting fruitful. »

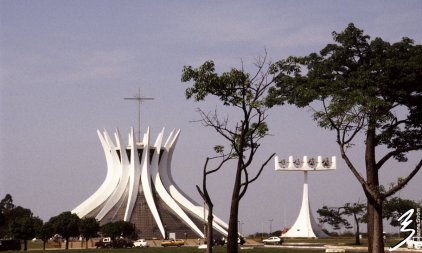

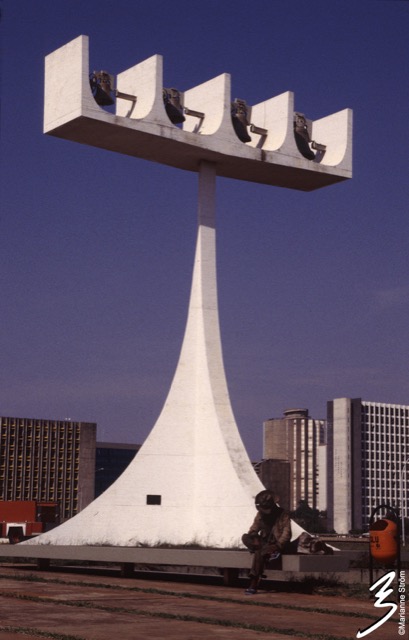

First we look at minarets, bell towers, bell houses and campaniles. These varied structures all serve to summon people and to bring them together.

The minaret, from which, five times a day, the muezzin chants the call to prayer, is a tower built next to or in a mosque. It may be circular, octagonal, or square. It is a distinctive feature of Islamic religious architecture. Its form was influenced by the towers of Early Christian churches in Syria.

Bells generally symbolise freedom. Their shape suggests the vault of heaven. Bells are often rung to summon people to prayer in Christian churches. They are hung in free-standing campaniles, or in the belfries or bell towers of churches.

Bell houses are often part of the compound of Buddhist temples. The wooden bell house has certain analogies with Chinese and Japanese pagodas. Bells may be rung hourly, daily, or just once a year. Some of the oldest free-standing wooden bell towers in Northern Europe, for example in Christian churches in Norway, have a striking likeness to Buddhist bell houses of Asia!

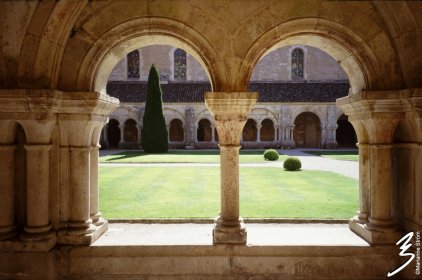

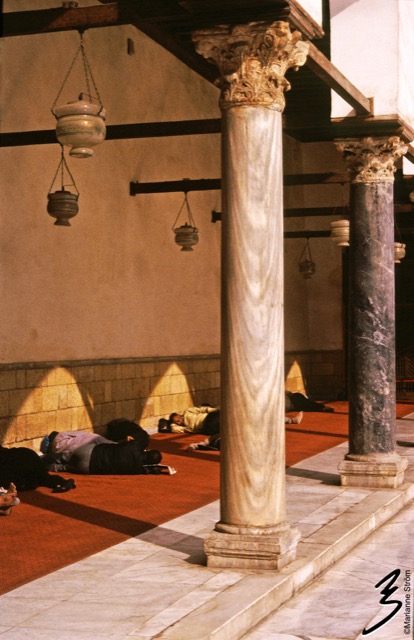

Next we come to arches, columns and capitals, all basic architectural elements of sacred structures. Columns, supporters of the «heavenly vault», upraise the arch and the vault, symbols of heaven in contrast with earth. At the top of the column, the capital holds a position «in between» heaven and earth.

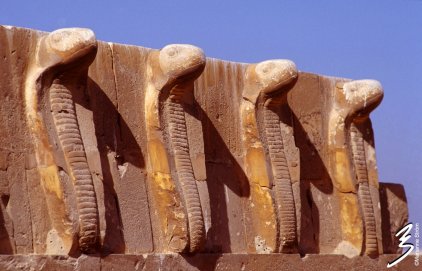

Dragons and serpents connote both good and evil. Associated with evil, we find in Greek mythology serpents strangle Laocoon and his two sons. We find the serpent in the biblical garden of Paradise, and the dragon being slayed by St George and St Michel.

Throughout the world the dragon/serpent plays the opposite to the demoniac, the malicious and the devourer.

In Ancient Egypt, for instance, the cobra stands in the front line: the Cobra frieze of the Chamber of Blue Tiles, Pyramid of Saqqara, recalls the snake goddess Uto. This protector-goddess, associated with the cobra, spits out her venom against the enemies of the king she protects.

In China, dragons bring luck and fortune and are the symbol of wisdom and fertility. These fire-blazing, hissing creatures often occupy the temple ridges from where they protect the sacred sites.

In Northern Europe, however, the deterrent dragonheads on prows of Viking ships and on ridges of their sacred sites, spread terror into the souls of the enemies.

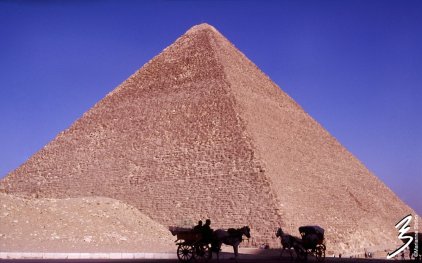

At the temple of Quetzalcoatl (the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, in Teotihuacán, Mexico) the head of the snake emerges from a «solar daisy», jaw open, next to the masque of Tlaloc, the Rain God, with his goggle eyes. The cult of the serpent regards the main god, God of Sun, who expresses himself in the construction of the pyramids, representing the victory of good over evil, light over darkness, knowledge over ignorance, the rising of the Sun God in the heavens.

In all civilisations and cultures man has expressed a need for memorials serving to help him to remember and pay respect to ancestors and to gods, spirits and events. Some memorials are monumental and timeless like the pyramids, «Man fears Time, yet Time fears Pyramids», says an Egyptian proverb. Others are small and ephemeral, like the «animita» (small memorial) at the roadside.